Epictetus was a Roman teacher and philosopher, born a slave, who lived from 55 – 135 A.D. He was famous for his wit as well as for a slim manual he wrote entitled ‘The Art of Living’. Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius was one of his students; not bad for a former slave, eh? I found a copy of this little book of his writings in a thrift shop; it’s the kind of thing you can read in a day, less than a day. My favorite of his many maxims for how to best master the difficult task of living, the art of being a human being, is to ‘forgive yourself over and over and over again. Then try to do better next time.’ Epictetus also exhorts us to forgive others, over and over, again and again. As with all maxims, I suppose, it makes so much sense, common sense, yet it is also typically much easier in the reading and agreeing with than it is in the execution. But I do, I try, to forgive and to do better next time, forgiving myself and forgiving others, over and over, again and again. And, once that’s done, and it’s never entirely done, I start again.

We were best friends for almost twenty years, and I loved him. We’d fallen out, though, and I did not see him except in my dreams, two of which arrived hand in hand with waking tears, one right on top of the other, just before he died of AIDs in 1993. I did not know he was dying; would it have made a difference? Yes. Of course. After having the dreams, vivid, real, painful, I tried to call him, to get in touch. But he’d disappeared, all the old the lines were disconnected, and I was ashamed, and angry at him still. I was an idiot.

In one of my dreams from that time he was there, on the front lawn of my childhood home, walking toward me across the brilliant green vastness of that so familiar space, also gone – sold off by then, all the way from the pool to the patio of the house, where we hugged as if we would never let go, and I woke sobbing. Where is my friend? I need my friend. In the other dream I was performing in a nightclub, singing, and I got stuck, unable to remember the words of a song I’d performed a hundred times or more, and there he was in the corner of the shadowed room, standing up, singing the words, helping me, moving toward me again across another familiar landscape – and abruptly the show was done, the room empty, and we were alone, best friends together once more, sharing confidences and stories as we’d so often done, laughing and whispering in a dark nighttime space that stank of perfume, poppers, booze, and cigarettes.

As for the falling out, I’d sublet an apartment from him in midtown and he’d stopped paying the rent to the landlord without telling me; six months or more went by until one day I came home to an eviction notice pasted to the door. I was dumbfounded, furious, betrayed. How could you do this to me? What have you done with the money I have been sending you every month? He was angry as well, and unrepentant. We’d been room-mates years earlier and almost lost our friendship over money then, an inconsequential amount I’d finally given in on because I loved him, and wanted to preserve the relationship, as I’d said at the time through slightly gritted teeth, and we’d – our friendship – survived the moment. But this was different. What I did not know, what he did not tell me, and I did not ask, was that his disease was advancing rapidly; he was leaving his job and his life in NYC to return to our adolescent stomping grounds in the Catskills to live out as long as he had left, which was a year – maybe two – I can’t recall. Life extending and saving drugs had yet to be invented, and he was running out of time. He was dying.

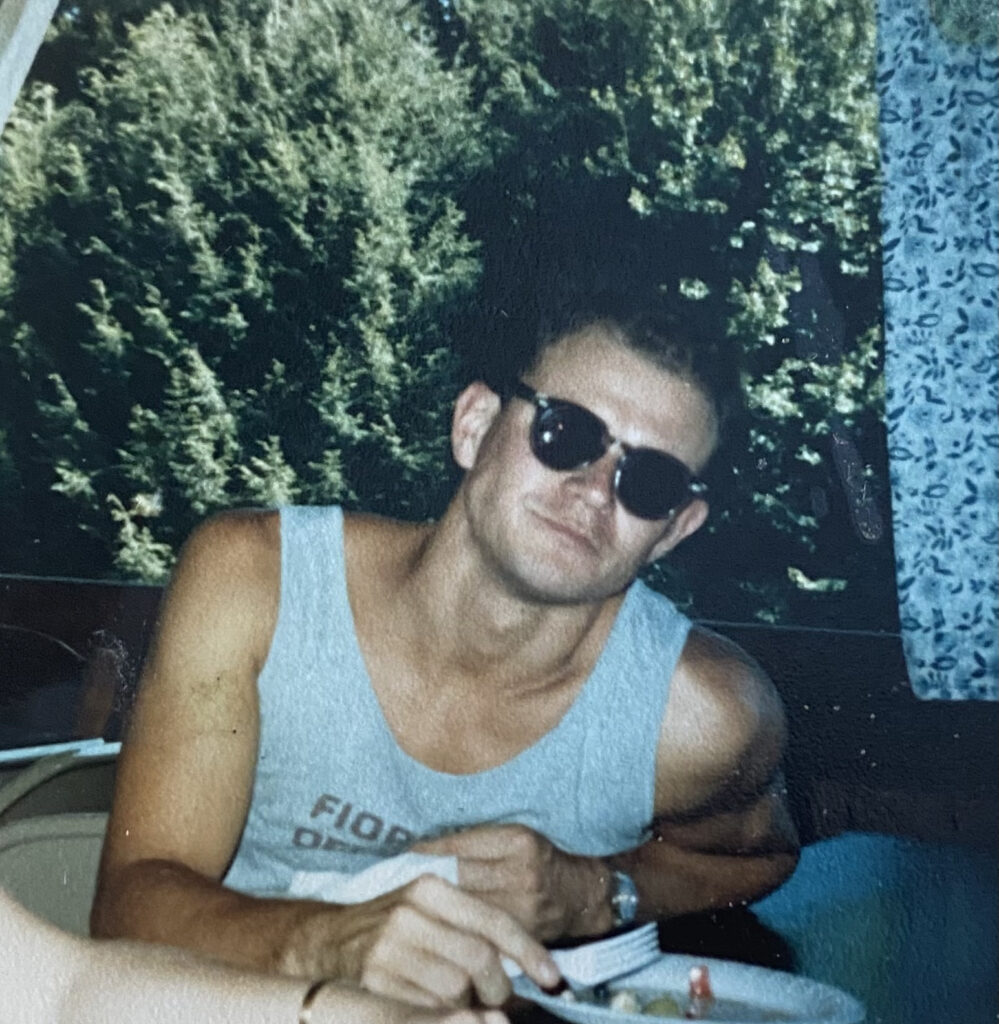

I have decided to think of our falling out as protection, as an almost good thing, because this thought gives me some comfort, which I seek in this as in many losses in my life so far. We were young and fabulous together, and now all I remember is how he was when we met and knew one another best, my forever young and handsome friend with the killer sweet smile. Neither one of us, vain silly creatures that we were (and me, still am), would have wanted to see how the story ended, how old and scruffy, saggy and sad, we’d get to be. Ear hair? Yick. Stretch marks on an 80-year-old tummy? Blech. And I comfort myself by thinking he would not have wanted me to see him at 85 pounds, which was his weight when he died, and I hope I am right, as I am, occasionally.

His family arrived in our tiny town the summer before our Junior year. He, his mom and step-dad, a very young half-brother who was not yet in school and three full siblings, pretty much all in a row, with Mark in my class, his sister Kim in 10th grade, his brother Mike another freshman in my younger sister’s class, and his baby sister Tammy in 7th grade. In an area as rural as ours, with a school whose total population was a little more than 800 kids, K – 12, a new family was big news, and everyone wanted to know who they were, where they’d come from, and what they looked like, especially Mark as the oldest boy, for he was a junior and therefore eligible to be the boyfriend of any number of girls, older and younger. It was September of 1975, and we were all idiots.

The usual happened: he was glommed upon right away by a few of the boys, but especially by two girls in my class. Their initial possessiveness would, I knew, fade, as his small school ‘celebrity’ and newness naturally and inevitably ebbed away. I pointedly ignored him, and kept on living my life. I’d like to claim this a was brilliant, deliberate strategy on my part but it wasn’t. I just couldn’t (still can’t) play games, create a friendship out of nowhere and nothing, and for me the fact that he was new to town didn’t make him any more or less interesting than my other classmates, most of whom I’d known since Kindergarten, if not before. And besides, who was he? Why should I make a fuss? Why would I? Why not let it happen when – and if – it happened? I refused to make a fuss over some random ‘new’ guy.

And then one day that fall, I arrived almost late and a little out of breath in history class, which we shared. I remember that the room, facing southeast, was full of sunlight; it was also my homeroom that year. He’d ended up in a seat directly behind me for the semester, and I made eye contact briefly with him, the new kid, Mark What’s-his-name, whereupon I sat down and pretty much died. The look in his eyes was so hurt, so filled with, ‘Why?’, and I didn’t want that! I wasn’t ignoring him to make him feel like shit; I was just being my usual highhanded, stiff-arsed self, but in that instant, I saw that I was hurting him, that I had the power to hurt him, this stranger, and I felt ashamed.

I turned. – ‘So, what’s your name again?’ He was clearly stunned. – ‘Mark’. – ‘Yeah, right, okay, so you’re from Pennsylvania?’ (I heard this from our classmates, and my mom) – ‘Yeah.’ – -‘And what day were you born?’ (I was into astrology, still am) – ‘August 15th’ – ‘That’s the same day as my brother, Fred! He’s a senior. You’re a Leo!’ – ‘Yeah, I guess. Yeah.’ – ‘Good. I love Leos, love’ and I reached over the back of my chair, and put my hand on both of his, which were clasped together on his desk, – ‘We’re going to be best friends, I just know it. So, there you have it.’ Or words to that effect. And, I did know it, in that moment. And, I was right. I occasionally am.

During our friendship, we did a lot together, but mostly we talked and laughed, we danced and listened to music, we performed in high school plays and intermittently came together or corresponded through the long years of college in cold, distant places, Syracuse (me) and Pittsburgh (him). Later we lived together on the Upper West Side in an apartment building that should have scared the shit out of both of us, the neighborhood was that bad in 1983, ‘84, and ‘85 but we were pioneers, leaving our small town and relatively cradled college experiences to forge new lives, different lives – and pioneers are never afraid. We were idiots.

I don’t remember when he came out to me; it might have been by letter, from Pennsylvania, where he was studying graphic arts. We lost touch a little in the months after high school, in times before email, cell phones, and Facebook, but I’m pretty sure I already knew his ‘news’, in my gut and via the loose but strangling hometown grapevine. I’d gone off to study theatre and was surrounded by gay men – and women – and while I held on to my childish fiction that all people were like mom and dad, as in straight, through my first two years of theatre training, by Junior year – when one of my female teachers both fell in love with and confessed her love to me (Holy crap! Women can be gay?! I was an idiot) – I’d wisened up a tad. Yet I still waited to hear it from him, the horse’s mouth as it were.

That he was ashamed was clear. And I don’t know that I was particularly sensitive or kind to him in that moment; he was my friend, I loved him and he was gay, whatever, no big deal. It made sense, and my acceptance was casual, because, y’know, so what? Anyway, I had always known, sort of, reminding him that when he’d dated a classmate of ours, briefly, even going so far as to take her to Junior Prom, it had baffled me to my core. Huh!? You’re dating her? This makes no sense. Something does not compute. It was inauthentic, even if I couldn’t put my finger on or articulate why. As I had done when he arrived, I chose to ignore their relationship, acting like it didn’t exist. It just felt wrong, was wrong, somehow, and although everyone thought I was jealous, it wasn’t that. And, it didn’t last.

I did not know then that he was in therapy; I did not know then that his mother regularly beat him with a thick leather belt; I did not know then that she told him time and again that she would rather he was dead than gay. My heart breaks even just to write that, and at the end she came through for him, when I was unaware and dreaming, only, of my friend.

I will never as long as I live forget his grandmother – his mummy’s mum – at his wake. She was in her 70s or 80s, I think, and as my pal Epictetus says – and I remind myself daily – one must not just forgive oneself but also work to forgive other people over and over again, and then begin once more to forgive, and forgive again. And yet. It can be such hard work. The wake was held in the house he shared with his partner in Ulster County, New York, on the edge of the Catskills where we’d met and I’d grown up. I was, after the formal ceremony, already on my way to being very, very drunk, despite the fact that I had to drive back to the city after the ‘party’. His grannie approached me to reminisce about our friendship, Mark’s and mine, and to tell me that they – his family – had always thought and hoped that I was ‘the one’. – No, no, not the one, not the right equipment, duckie. So that was never gonna happen, right? Okay? He was gay. Without skipping a beat, grannie said – ‘I think God will forgive him for what he did and what he was.’ – ‘What?!’ I said. ‘What?’ Mark’s mother had been watching from about five feet away, an ‘oh dear’ look on her face, and swooped in to end our conversation, perhaps seeing the look on my face, the face of someone who was drunk, grieving, and about to rip that old witch a new one. Forgive him?!!

1993. AIDs and AIDs deaths were rampant in those days, and many people were waking up to just how many gay men they knew, and loved, forcing them to deal, and deal compassionately and realistically, with the fact of homosexuality and their feelings about the same for, perhaps, the first time. Not that all – by a long shot – dealt well, or compassionately; many, too many, turned away. Still, this awakening, this awareness, was an awakening that I believe helped spur the changes of the next few decades, was the glass half full of some kind of special poison and history altering tilt in the culture and media’s version of events. Gay-ness existed, and people, people you say you love and care about, who love you, are dying so make up your fucking minds already. Will you, will we, continue to deny or denounce the existence of our friends, brothers, uncles, cousins, sons – and our gay sisters, cousins, mothers etc., etc. – due to blind prejudice? To ignorance and fear? How much forgiveness will we require, if we fall short in this way, especially at this time, for these – our dying friends? Our dying family?

Yet for all Mark and I shared – all the conversations and time, spooning naps and cab rides home after late nights at various clubs, 4 or 5 or 6 a.m. breakfasts – there was still so much he kept hidden from me, and, truthfully, I from him. But, but! We talked about what we were attracted to in men! We danced the night away at Limelight and 54! He took me to the Saint! Twice! We were in therapy! We analyzed our dreams! We shared a bathroom! I thought I’d seen and heard it all, but I hadn’t. How could I? Nor had I shared it all, my own story. And how much of anyone else’s pain, or joy, do we ever really know?

On our way to our 10th high school reunion we got incredibly high, the kind of high where we laughed so hard I almost drove off the NYS Thruway. It was one of those weird-ass, film-worthy weekends, both eye opening and challenging, as several of our former classmates and peers confessed their gay fantasies or extra-marital high-jinks to us, among other uncomfortable and truly head-shaking moments. Did our tee-shirts say, ‘Hey, we live in NYC, so bring it on, people! You can tell us anything, no judgement!’, because they, our classmates, sure did. Later I took Mark to visit an old friend of my family, the doctor who’d delivered me and my siblings, and this man, then in his 70s, was very, very kind to him, when we spoke of Mark being gay. This kind and beloved healer, who’d worked for years at a college down south after leaving our small town, really had seen it all, and as far as he could tell, being gay was as normal as not being gay, just less common. It was a great moment. 1987. I was so glad I insisted Mark accompany me on this side trip, skipping another party with our ‘old buddies’. I saw how much it meant to him, acceptance and affirmation from an older man, a man closer to his grandfather’s or father’s age, his father the old school Southern Baptist preacher who’d long ago disowned his gay eldest son, and namesake.

We were sober on the ride back in every possible way. Somewhere on the road, Mark turned to look at me, I was driving, and asked me why I thought he was gay. Now this was something I’d thought about time and again. I was an idiot. – Oh my God, ohmigawd, I’m so glad you asked! Yay! Well! Okay. Yes, well, ok, so! Y’know, you were born gay, absolutely, 100%, of course, and yes, clearly there are genetics at work here, I guess, and then, let’s be real, dude, your mother is like a hyper-sexualized version of Liz Taylor only kind of, sorry, white-trash-y, no offense, the hair alone, the booze, the caftans, the drama! And you were her oldest, her ‘little man’ after the divorce from your dad when you were only, what? 6? 5? Scary times, pal, and then there’s the whole Baptist preacher absent father thing, and who knows, really. Born. Genetics. Mom. Dad. Crazy town. Religion. Southern Baptists! These are just random thoughts

(I finally shut up). So. Why do you think you’re gay?

-Yes, he said, yes, all of that. Those. I mean, I knew when I was a child, that I was – different. – Of course, you did, because you schmart, Markie, you so schmart! – And. – And? – And I knew – Yeah? You knew? – I knew I was different in a way I wasn’t supposed to be. – Oh fuck that. Just fuck that. That’s crazy. – And. – And? – Well, you know when my parents divorced we moved in with my grandparents. – Yeah, for a couple of years, and? – And my uncle – The minister? Your mother’s brother? Your grannie’s favorite? – Yes. My uncle. He lived next door. – Right. I remember you telling me that. – And when I was 7 he started having sex with me. – What?! What?! What?! – Yeah. Until I was 11 and mom married Walt. – What?! What?! – Yeah. So, I don’t know. -Oh my God, Mark, oh my God. -And my mother knew. –What?! What?! What?!! – I mean, I’m pretty sure she knew. – What?! What?! What? How?! How?! – Yeah. Calm down. – Calm down, calm down?! – She told me once, we were setting the table for dinner, that I didn’t have to do it, with my uncle, if I didn’t want to. – What?!Fuck! What the?! Fuck! Fuck, Fuck Mark! – Calm down! – Calm down, calm down! Why didn’t you ever tell me this before? Why? – Because. – Because? – Because I thought you’d hate me. – What? Oh my God Mark. Oh my God. Hate you? Hate you? You didn’t do anything wrong! Jesus F-ing Christ! It makes me love you more. It makes me love you more.

Of course there was more to tell, that he pretended not to hear his mother, what she said about Mark, and her brother, that he didn’t have to do it, if he didn’t want to, that his younger brother and sisters had also been abused but he, Mark, was his uncle’s favorite, that his mother was only twenty-three or four at the time, with four young children to support, that she hadn’t finished high school, had no money, was working as a waitress, barely getting by even while living rent free with his grandparents, and that he’d seen his uncle rather recently, when he was visiting Pennsylvania, clearing out his grandparents’ garage after his grandfather’s death, when his uncle chose to tell my dear friend ‘I feel responsible for what you are, for what you’ve become’, and, just as with his mother’s statement over the dining table, Mark chose not to hear him, to keep on doing what he was doing, because acknowledging any of it, any of it, was simply not possible.

He said all of this to me, while my hands gripped the steering wheel, and I stared straight ahead, because if I’d looked at him, in my rage and my sorrow, I would’ve killed us both, driving off the thruway, crashing that shitty white rental car. – So yeah, he said, I’ve wondered if, I might’ve been different, if I would’ve had, or maybe even made another choice, if that hadn’t happened. Y’know? Been straight. – Oh Mark. Oh Mark.

And, of course, there was more. How when his mom met and married Walt they’d all gone off on a cruise together, the new happy family, sailing blissfully and safely away from the nightmare back home, on into another life – except that on the cruise a twenty-five or six-year-old steward seduced my friend. – Dammit, Mark, that’s not seduction, you were eleven, you were a child! You were a child. Jesus H. Christ!

As I recall, we spent much of the rest of the drive back to New York in silence, Mark staring out the window, while I drove and wept.

We do not know what goes on in other peoples’ lives and neighborhoods and homes and hearts. Yet how could I have ignored him, this sweet, gorgeous soul, even for two or three or five weeks, back in 1975? How could I have let our friendship lapse at the close, no matter how much money was involved? He was my friend and I loved him. If only he’d lived to see Will & Grace, Angels in America, marriage equality! If only he’d lived. Oh Mark. We were idiots. We were all idiots. I forgive myself and all others, again, and again, and again. And then, I begin once more.

“The secret of a full life is to live and relate to others as if they might not be there tomorrow, as if you might not be there tomorrow. It eliminates the vice of procrastination, the sin of postponement, failed communications, failed communions.” ~ Anaïs Nin

copyright Marjorie Miller 2016