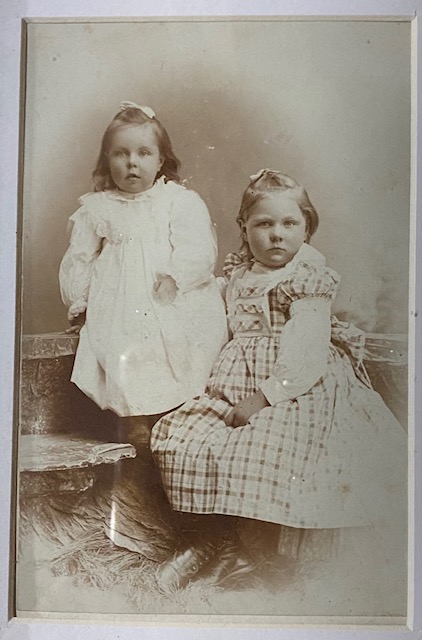

This photo is of is my grandmother, Marjorie Davidson, on the left, and her sister Martha, the elder by two years, circa 1894 or ’95. I love this picture because I love – loved – my grandmother, and because of the look of fierceness on Great Aunt Martha’s face, at least as I see it. I like to imagine that, as the older sister, Martha would have defended her little sis with all her might, but it could be that the photographer was socially inept, didn’t know how to treat little girls, or maybe he kept insisting she sparkle or smile, in which case I know exactly how she felt: men have been telling me to smile for years, and I have perfected a truly frightening grimace in response.

These sisters, Martha and Marjorie, were the best of friends their entire lives, although those lives took significantly different paths, and my grandmother outlived her beloved sister by over twenty years, living to be almost ninety-eight. My sense was that their parents were enlightened, good people, who loved all of their children, and were respected and loved in return. Martha and Marjorie were educated beyond what was much more conventional for the time; after graduating from high school in Monticello, N.Y, they attended Oneonta and Albany Normal Colleges, respectively, and they both went on to teach, Martha for many years in the Oneonta School District, in Otsego County, New York, and Marjorie on the eastern end of Long Island, in the Hampton Bay S. D.

I don’t know how my great aunt met her future husband, Ward Woolheaver, but I know she waited many years to marry him because in true gothic novel fashion, he was married already, with a wife in a mental institution, a wife he would not divorce her in her diminished and vulnerable state. And so, having met and fallen in love they waited, until after many years the first Mrs. W passed away, and Ward was free to wed. By then Martha was in her fifties, and I believe Ward was at least a decade older. From all reports, my grandmother’s, my dad’s, and my mom’s, Ward and Martha had a great life together, buying a home in Franklin, New York, where they loved to socialize with friends and family. It wasn’t a long marriage, however, as both of the pair were very heavy smokers; I clearly remember Martha wreathed in a cloud of smoke, with a long, schmancy cigarette holder, upswept hair, and chunky bracelets. So stylish, I thought, even if I also thought I was going to die when she visited: along with my dad’s pipe, fresh air inside our house during those dinners was in very short supply. Her husband, Ward, died first, I’m not sure what year, but I know that Aunt Martha lived alone for at least a decade – moving to a ground floor apartment in Oneonta – before succumbing to lung cancer in 1968.

I do know that my grandmother met my grandfather when he returned from World War I to finish his high school education. She was his Latin and physics teacher, and by the time he completed his schooling, he was almost twenty-three, and she was almost twenty-six, and they’d fallen in love. She urged him to go on to college, he was so bright, but his dream was to farm, so she left teaching to become a farmer’s wife. According to my dad’s first cousin (and mine once-removed, I think is how it works), my grandmother worked harder on the farm than three hired hands put together, and I believe it. Her husband, my grandfather, was an extremely difficult man she loved a lot, as did I, a man who was volatile and abusive, expecting absolute obedience from his wife and children. He was insecure and ego driven in a way she was not, picking fights whenever and wherever he could, at home, and in public. He didn’t know how to be loved; he feared it. His favorite brother, Fred, had died suddenly at eighteen, going septic from a scratch on his cheek, one minute perfectly vital and alive, then dead less than forty-eight hours later. I don’t think my grandfather, sixteen at the time, ever recovered from the loss. Like Marjorie and Martha, the brothers had been best friends, and I’ve often wondered if he felt that Fred, who he and everyone else had loved, haunted every room in the construct of his own much more difficult temperament.

But I digress.

My grandparents married in 1921, and bought the farm the same year, where they grew cauliflower and kept dairy cows until retiring in the mid-fifties. Their fourth child, my uncle Jay, was born in 1926; he joined an older brother, and two older sisters, Bill, Betty and Martha, at home in New Kingston, the latter named after my grandmother’s sister. Aunt Martha visited to meet baby Jay at the farm in 1926 or possibly even 1927. I’m not sure; the roads were less traveled, and much less travelable back in the day, thus what is a forty-minute ride to Oneonta now was at least ninety minutes back then, if the weather was clear.

Great Aunt Martha wasn’t a huge fan of her brother-in-law, and from what I’ve heard, and the little I remember, the feeling was entirely mutual. Still, she very much loved her baby sister, prioritizing that relationship by keeping in touch through letters and calls, while making visits to the farm whenever she could, and could stomach putting up with her sister’s bully of a husband, always trying to pick a fight. Unlike her sister, Martha had not learned, nor would she ever learn, that when it came to her kid sister’s husband it might be better to keep her tongue behind her teeth. Still defending her sister, Martha picked fights right back at him, and for that, I am deeply grateful. You go girl.

As the story went, visiting the farm in ‘27, and after examining and exclaiming over baby Jay, Great Aunt Martha said to my grandfather, ‘Well, I hope that’s it, Bill.’

‘What do you mean Martha?’

‘I said, I hope that’s it. I hope you’re going to give Marge a rest.’

‘What does that mean, Martha? Give her a rest?’

And where was grandma at this stage? Tending to the baby? Hiding out in the kitchen or living room? From many other confrontations I witnessed between my grandfather and any one of his many sworn enemies (a long list that included my mother), I believe she would be sitting right there witnessing it all, giving nothing away, a female embodiment of the Rock of Gibraltar, albeit a rock with a slight smile on its face. (You go girl.)

‘I mean: I hope this is it. As in no more children.’

Nine months later, maybe ten, my father was born.

All hail Great Aunt Martha! Without you, I would not be here, you darling, pugnacious little girl, you loving sister, you fight picker, you marvel of a woman. You, Martha the First, rejecter of sparkle. All hail!